My Battle with Spain’s Neo-Nazi Underground

In the mid-90s, while most American teenagers were worrying about curfews and mixtapes, I was dodging fascists in the streets of Madrid.

At sixteen years old, I was third on a neo-Nazi hit list circulated by Bases Autónomas—Spain’s most violent skinhead organization at the time. They called me “Americano Marrano”—a racist, piggish slur meant to dehumanize me and mark me for elimination. These were not empty threats. Bases Autónomas wasn’t some online hate forum or angry meme page. It was a coordinated neo-Nazi movement that published hit lists with full names, home addresses, phone numbers, even license plates. The list I was on targeted over 100 people, from Black and immigrant youth to sex workers, anarchists, journalists, separatists, and communists. I just happened to be one of the youngest and loudest among them.

They wanted us gone—and they didn’t hide it.

The group’s underground zine, Cirrosis, encouraged violent action. They named bars to be firebombed. They listed the addresses of activists to be attacked. They gave step-by-step instructions on how to infiltrate our spaces—“Dress like an anarchist, scream slogans like ‘Gora ETA,’ and leave with a notebook full of addresses.” They encouraged stalking family members. They fantasized about burning us alive.

I saw that fantasy attempted firsthand.

One day, I watched my primary antagonist—a violent Nazi skinhead known as El Mallorquín—hang a kid from a fence and pour lighter fluid on him. He struck a match. We got to the boy just in time. A street battle followed, and we pushed El Mallorquín and his crew out. It wasn’t the first time I crossed paths with him, and it wouldn’t be the last. He was eventually arrested for murder in 1995 alongside two other neo-Nazis. That arrest made headlines in El País, but what didn’t make the news was the day we took the fight back to them.

During Anarchy Week, I helped organize the largest bonehead hunt Madrid had ever seen—almost 3,000 of us hit the streets. We ran it like a protest, but make no mistake: it was a show of force. The fascists, who used to swarm and intimidate, scattered like rats. That moment didn’t make the newspapers. There’s no grainy footage or viral clips. But we remember. We were there.

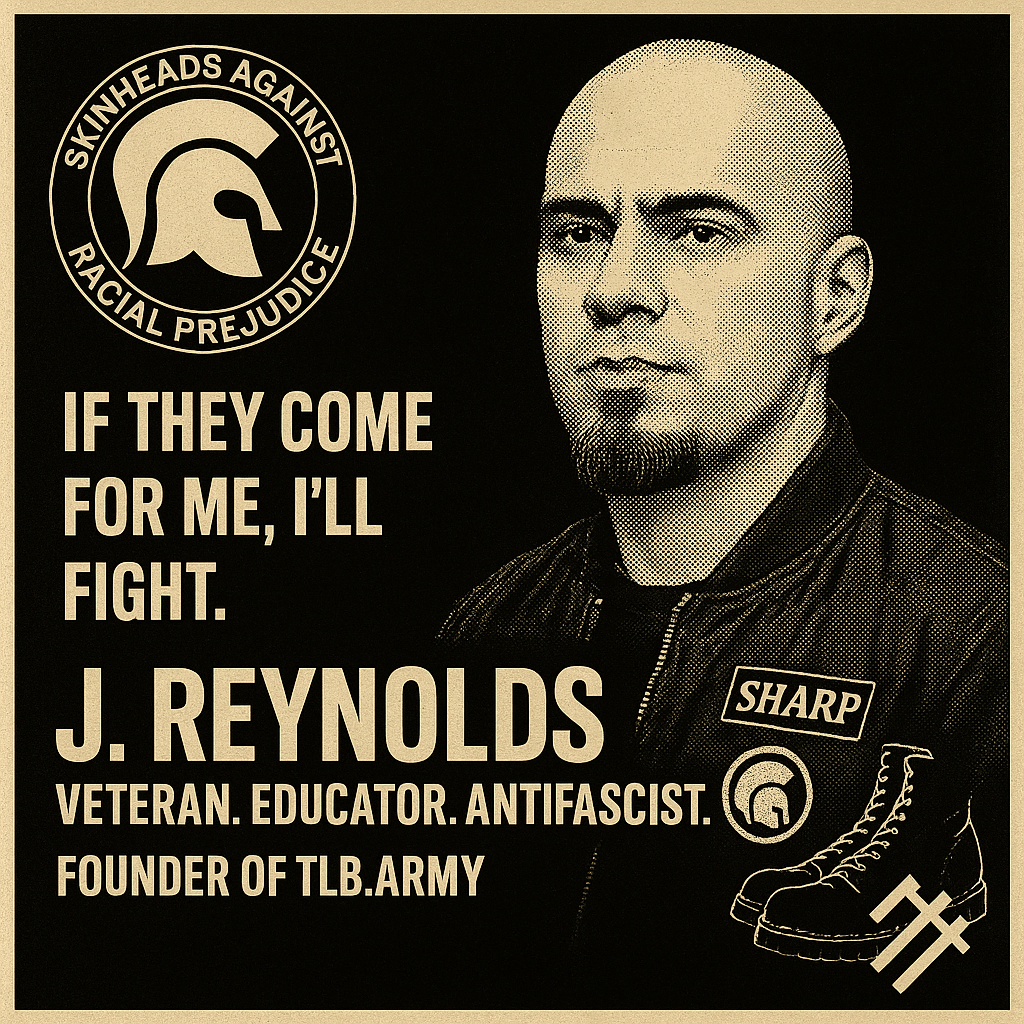

My own inclusion on the hit list was published publicly, and a journalist managed to capture a quote from me at the time:

I said it without hesitation. I meant every word.

Still, it wasn’t easy. I won many fights, but not all of them. My biggest adversary, El Mallorquín, was ruthless. But there was another figure—his supposed brother, who went by Irra el Loco. His nickname, The Crazy One, wasn’t for show. He had a reputation for street violence and unpredictability, but our encounters were… complicated. He respected the danger I represented—not so much because of me, but because of my ties to another American, Johnny.

Johnny was a Black American living in Spain. A gangster in his own right. He never flexed unnecessarily, but everyone knew not to cross him. He had reach, respect, and real power. He always said, “It’s just business.” The Nazis wanted nothing to do with him. They were terrified. And because I was close to him—even peripherally—I became radioactive to them in a way they didn’t know how to handle.

My visa expired in 1996. I returned to the U.S. that December. Coincidentally—or maybe not—that same year Bases Autónomas dissolved and scattered underground. I’m not claiming credit, but I’ll say this: It wasn’t luck. It was a collective effort by punks, anarchists, antifascists, immigrants, and everyday people who refused to stay silent. We didn’t call ourselves heroes. We just didn’t back down.

And while the state looked the other way—while police failed to warn us, protect us, or even acknowledge that we were in danger—we protected each other. Bar owners condemned the silence. Unionists called for economic resistance. And some, like me, said it plainly:

“They’re not just boneheads. They’re organized, violent, and dangerous. But if they really want, to fuck around, I’ll gladly help them find out.”

Now, nearly 30 years later, I carry the scars and pride of that era. Some memories haunt me. Others, I wear like armor.

There’s no plaque, no medal, no documentary for what we did. But I’ll say it again—if they come for me, or mine, or my people.

I’ll fight, to the death, theirs preferably.

49 Comments

fxh2j0

uqd285

Good shout.

9d1nty

full spectrum cbd gummies area 52

thc gummies

thca carts area 52

disposable weed pen area 52

thcv gummies area 52

buy thca area 52

cbd gummies for sleep area 52

thca diamonds area 52

best sativa thc edibles area 52

hybrid gummies area 52

infused pre rolls area 52

thc microdose gummies area 52

indica gummies area 52

thca gummies area 52

legal mushroom gummies area 52

thc tincture area 52

snow caps area 52

liquid thc area 52

distillate carts area 52

live resin carts area 52

live resin area 52

liquid diamonds area 52

live resin gummies area 52

live rosin gummies area 52

mood thc gummies area 52

hybrid carts area 52

best pre rolls area 52

best indica thc weed pens area 52

thc oil area 52

weed vape area 52

best thca area 52

2 gram carts area 52

amanita muscaria gummies area 52

sativa vape area 52

1 gram carts area 52

thca disposable area 52

DO

CA

Nice

thc gummies for anxiety area 52

thc gummies for sleep area 52

thc gummies for pain area 52

DO

анонимный детский психолог онлайн

https://telegra.ph/Uzly-vala-dlya-separatorov-07-31-2