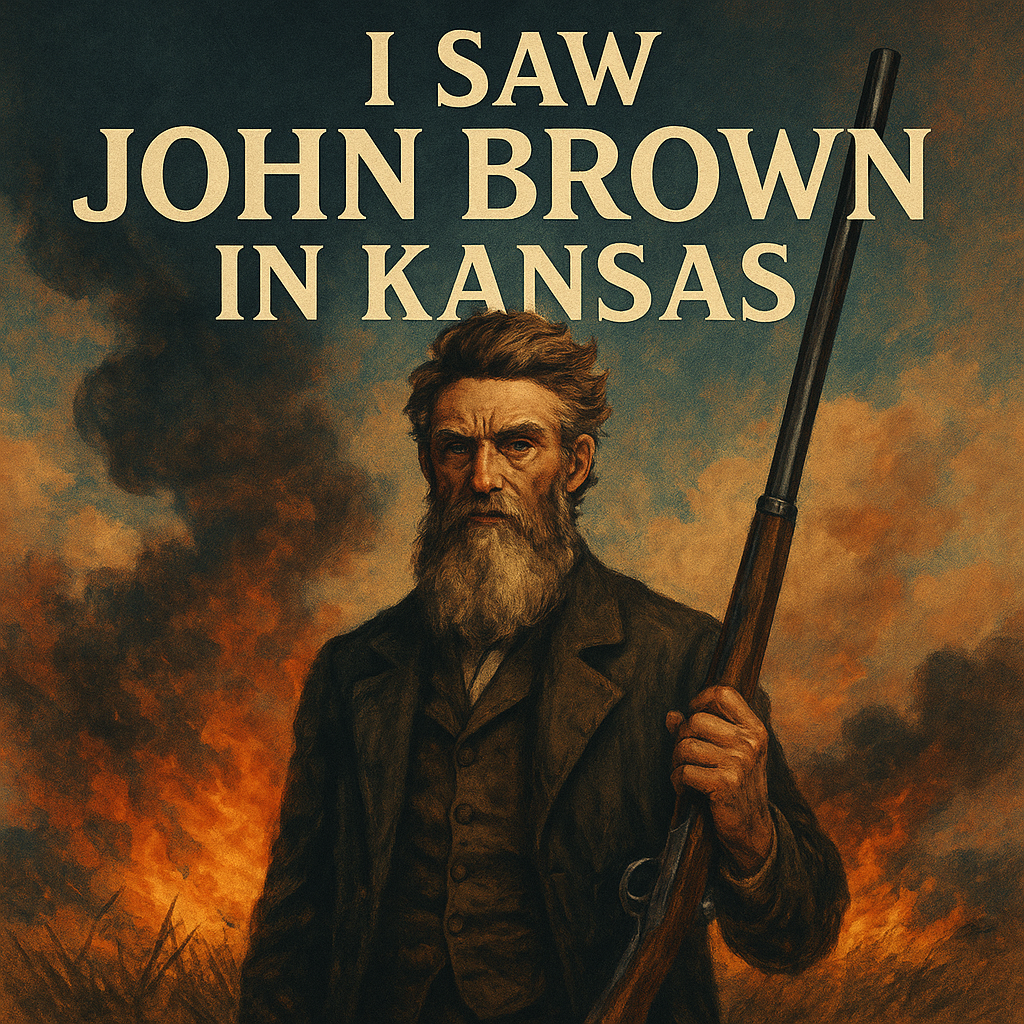

I’ll never forget the smell first—burnt powder, sweat, and blood mixing into that heavy Kansas heat. The prairie don’t give a damn about your convictions; it just sways in the wind while men tear each other apart beneath it. And that’s where I found myself, a nobody with calloused hands and trembling knees, watching a wild-eyed prophet named John Brown carve his name into history with fire and steel.

I wasn’t a fighter then. Not really. Just a farmhand out near Osawatomie, trying to make enough to keep my mother fed and my sister clothed. Kansas was supposed to be opportunity. Fresh land, wide skies, a man’s chance at building something. But opportunity had been poisoned before the first seed ever touched the soil. The whole territory was a powder keg—pro-slavery bastards flooding in from Missouri with rifles and whiskey breath, free-state settlers coming in with wagons full of Bibles and plows. And me? I just wanted peace. Thought maybe I could keep my head down, stay out of the storm. But Kansas doesn’t let you stay neutral. Not then. Not ever.

That’s when I saw him. John Brown.

Christ, he didn’t look like much at first—old man, beard wild as prairie brush, eyes like hot coals that never went out. But when he spoke, fuck me, it was like Moses come down from the mountain, except with a rifle slung across his shoulder. He didn’t ask you to follow. He commanded you, without a word. Some men have that gravity, like the Earth itself tilts toward them.

The night I truly witnessed him was bloody, and I won’t lie to you—it shook me to my bones. We were huddled in a shack, maybe a dozen of us, when word came that pro-slavery men had been terrorizing settlers up and down the creek. Burned homes. Beat folks half to death. Threatened to drag free-soilers south in chains. You could hear the rage crackling off Brown before he said a word. He stood, and the room stilled.

“They want war?” he growled. “Then by God, we’ll give it to them.”

Some whispered he was mad. Others said he was touched by the Lord himself. But when he raised that sword—yes, a goddamn broadsword, old and heavy—you could feel history lean forward to listen.

That night became what folks later called the Pottawatomie Massacre. Five pro-slavery men dead by John Brown’s hand and ours, though I’ll tell you true, I barely swung my blade. My stomach churned, my hands shook, and I wondered if I’d just walked into hell. But Brown? He didn’t flinch. He said every drop of blood spilled was a down payment on freedom itself. And I believed him, even as I gagged on the iron stench of murder.

It wasn’t fun. It wasn’t glorious. It was ugly as sin. But looking back, I see it plain: he wasn’t just killing men, he was cutting through the illusion that slavery could be voted away, prayed away, reasoned away. Brown understood what so many pretended not to—slavery was war already. It had always been war. And he was damn well going to fight it.

After that night, nothing was the same. The pro-slavers came for us in waves, howling for vengeance. I fought beside Brown at Osawatomie when they burned the town to ash. Cannons roared, muskets cracked, and we were outnumbered five to one. I remember crouching behind a splintered fencepost, heart hammering so hard I thought it might burst. Brown strode through the chaos like a man possessed, firing calmly, shouting orders like thunder. When his own son Frederick fell—shot down before his eyes—he didn’t break. His face twisted with grief, but his hands stayed steady, his voice steady. He fought harder.

That broke something in me. Or maybe it built something. I don’t know. Watching a father lose his boy and still keep fighting for a greater cause—God help me, I swore right then I’d never turn away again.

And yet, Brown wasn’t all fire and fury. I saw him pray with trembling settlers, share bread with orphans, weep quietly when no one thought he was looking. He carried the weight of every death, friend and foe alike. But he believed, with a faith that could split mountains, that freedom was worth it all.

People later said he was a fanatic, a terrorist, a madman. Maybe he was. But standing there in Kansas, with the prairie burning and blood soaking the soil, I saw something else. I saw a man willing to match the brutality of slavery blow for blow, to stare evil in the face and not blink. Most men preach freedom in words. John Brown preached it in action.

And here’s the thing—they called him crazy, but he wasn’t wrong. Look at the arc of it all. Kansas bled, the nation fractured, and soon enough the Civil War swallowed everyone whole. What Brown did out there wasn’t madness—it was prophecy. He was the storm warning, the thunder before the deluge.

Sometimes, late at night, I still see his eyes. That burning coal fire, fierce and unyielding. I wonder if I’d have had the courage without him. Probably not. He lit something in all of us who followed, even those of us too weak or too scared to swing the blade. He made us believe freedom was worth the blood, the terror, the goddamn impossible fight.

Kansas taught me neutrality is a lie. It taught me that some evils can’t be compromised with, bargained with, or voted down. You either stand against them, or you’re complicit in them. John Brown knew that, lived that, and died for that.

And I—I was there. I saw the fire in his eyes, the blood on his hands, the unshakable resolve in his voice. I walked beside him through smoke and carnage. I hated it, feared it, and yet, God help me, I was inspired beyond measure.

So when people ask me who John Brown was, I tell them: He was the man who showed me freedom is never free, and neutrality is a coward’s comfort. He was madness and mercy, fury and faith, all wrapped in one bearded, battle-scarred body.

He was Kansas itself—wild, bloody, and unbreakable.

And I’ll be damned if I ever forget him.

4 Comments

7vbpr7

14khqm

0uhav3

wf1g4y